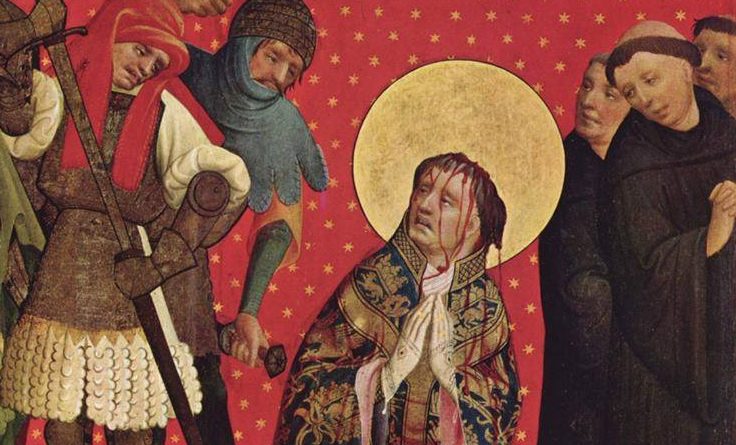

The Martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket by Edward Grim; Saint, Friend, and Biographer

Henry II became King of England and, upon the advice of Archbishop Theobald, made him his chancellor. Thomas and the King became great friends due to their mutual interests and love of luxury. Thomas even took up arms with King Henry when the monarch went to battle in Toulouse, and is said to have served well as a warrior. When Archbishop Theobald died in 1161, King Henry did all in his power to see that Thomas took over his archdiocese. Thomas was not happy about the idea but, urged on by Cardinal Henry of Pisa, was ordained priest on a Saturday in Whitweek, and was consecrated as Bishop the next day, Sunday, 3 June, 1162. After attaining the See of Canterbury, something changed in him. He gave up his former life of indulgence and focused on penance and prayer. His friendship with King Henry, however, became strained after he resisted various plans that Henry wanted to institute — but the issue that led to St. Thomas’s martyrdom concerned jurisdiction: King Henry wanted all clerics to assent to the Constitutions of Clarendon (1164) which asserted that the King, not the Church, had jurisdiction over criminal clerks. Thomas at first assented, but later stood tall and spoke out for the rights of the Church. Threatened with imprisonment or death, he fled to the Pope for a resolution to the matter, and then exiled himself for a few years in a French Cistercian abbey, devoting himself even more deeply to penance. While there, he also excommunicated the Bishops of London and Salisbury for siding with the King. An uneasy peace was worked out between Thomas and Henry, and so Thomas, amid the cheers of the local people, returned to Canterbury. But he refused to lift the censures against the Bishops who stood with the King against the Church.

.

SAINT THOMAS BECKET MARTYRDOM

.

Around this same time, the second most powerful cleric — Roger of York — had the King’s ear, and told him that as long as Thomas lived, the King would never have a tranquil kingdom. The King is said to have cried, “Who will rid me of this meddlesome priest?” — whereupon, four knights — William de Tracy, Richard Brito, Hugh de Moreville, and Reginald FitzUrse — who overheard the conversation set out to grant the King’s wishes. It was the afternoon of 29 December 1170 when the four knights entered Canterbury Cathedral. After the monks took [Thomas] through the doors of the church, the four aforementioned knights followed behind with a rapid pace. A certain subdeacon, Hugh the Evil-clerk, named for his wicked offense and armed with their malice, went with them — showing no reverence for either God or the saints because by following them he condoned their deed. When the holy archbishop entered the cathedral the monks who were glorifying God abandoned vespers — which they had begun to celebrate for God — and ran to their father whom they had heard was dead but they saw alive and unharmed. They hastened to close the doors of the church in order to bar the enemies from slaughtering the bishop, but the wondrous athlete turned toward them and ordered that the doors be opened. “It is not proper,” he said, “that a house of prayer, a church of Christ, be made a fortress since although it is not shut up, it serves as a fortification for his people; we will triumph over the enemy through suffering rather than by fighting — and we come to suffer, not to resist.”

.

Without delay the sacrilegious men entered the house of peace and reconciliation with swords drawn; indeed the sight alone as well as the rattle of arms inflicted not a small amount of horror on those who watched. And those knights who approached the confused and disordered people who had been observing vespers but, by now, had run toward the lethal spectacle exclaimed in a rage: “Where is Thomas Becket, traitor of the king and kingdom?”

.

No one responded and instantly they cried out more loudly, “Where is the archbishop?”

.

Unshaken he replied to this voice as it is written, “The righteous will be like a bold lion and free from fear,” he descended from the steps to which he had been taken by the monks who were fearful of the knights and said in an adequately audible voice, “Here I am, not a traitor of the king but a priest; why do you seek me?” And [Thomas], who had previously told them that he had no fear of them added, “Here I am ready to suffer in the name of He who redeemed me with His blood; God forbid that I should flee on account of your swords or that I should depart from righteousness.”

.

With these words — at the foot of a pillar — he turned to the right. On one side was the altar of the blessed mother of God, on the other the altar of the holy confessor Benedict — through whose example and prayers he had been crucified to the world and his lusts; he endured whatever the murderers did to him with such constancy of the soul that he seemed as if he were not of flesh. The murderers pursued him and asked, “Absolve and restore to communion those you have excommunicated and return to office those who have been suspended.”

.

To these words [Thomas] replied, “No penance has been made, so I will not absolve them.”

.

“Then you,” they said, “will now die and will suffer what you have earned.”

.

“And I,” he said, “am prepared to die for my Lord, so that in my blood the Church will attain liberty and peace; but in the name of Almighty God I forbid that you hurt my men, either cleric or layman, in any way.” The glorious martyr acted conscientiously with foresight for his men and prudently on his own behalf, so that no one near him would be hurt as he hastened toward Christ. It was fitting that the soldier of the Lord and the martyr of the Savior adhered to His words when he was sought by the impious, “If it is me you seek, let them leave.”

.

With rapid motion they laid sacrilegious hands on him, handling and dragging him roughly outside of the walls of the church so that there they would slay him or carry him from there as a prisoner, as they later confessed. But when it was not possible to easily move him from the column, he bravely pushed one [of the knights] who was pursuing and drawing near to him; he called him a panderer saying, “Don’t touch me, Rainaldus, you who owes me faith and obedience, you who foolishly follow your accomplices.”

.

On account of the rebuff the knight was suddenly set on fire with a terrible rage and, wielding a sword against the sacred crown said, “I don’t owe faith or obedience to you that is in opposition to the fealty I owe my lord king.” The invincible martyr — seeing that the hour which would bring the end to his miserable mortal life was at hand and already promised by God to be the next to receive the crown of immortality — with his neck bent as if he were in prayer and with his joined hands elevated above — commended himself and the cause of the Church to God, St. Mary, and the blessed martyr St. Denis. He had barely finished speaking when the impious knight, fearing that [Thomas] would be saved by the people and escape alive, suddenly set upon him and, shaving off the summit of his crown which the sacred chrism consecrated to God, he wounded the sacrificial lamb of God in the head; the lower arm of the writer was cut by the same blow. Indeed [the writer] stood firmly with the holy archbishop, holding him in his arms — while all the clerics and monks fled — until the one he had raised in opposition to the blow was severed. Behold the simplicity of the dove, behold the wisdom of the serpent in this martyr who presented his body to the killers so that he might keep his head, in other words his soul and the church, safe; nor would he devise a trick or a snare against the slayers of the flesh so that he might preserve himself because it was better that he be free from this nature! O worthy shepherd who so boldly set himself against the attacks of wolves so that the sheep might not be torn to pieces! and because he abandoned the world, the world — wanting to overpower him — unknowingly elevated him. Then, with another blow received on the head, he remained firm. But with the third the stricken martyr bent his knees and elbows, offering himself as a living sacrifice, saying in a low voice, “For the Name of Jesus and the protection of the Church I am ready to embrace death.”

.

But the third knight inflicted a grave wound on the fallen one; with this blow he shattered the sword on the stone and his crown, which was large, separated from his head so that the blood turned white from the brain yet no less did the brain turn red from the blood; it purpled the appearance of the church with the colors of the lily and the rose, the colors of the Virgin and Mother and the life and death of the confessor and martyr. The fourth knight drove away those who were gathering so that the others could finish the murder more freely and boldly. The fifth — not a knight but a cleric who entered with the knights — so that a fifth blow might not be spared him who had imitated Christ in other things, placed his foot on the neck of the holy priest and precious martyr and (it is horrible to say) scattered the brains with the blood across the floor, exclaiming to the rest, “We can leave this place, knights, he will not get up again.”

.

But during all these incredible things the martyr displayed the virtue of perseverance. Neither his hand nor clothes indicated that he had opposed a murderer — as is often the case in human weakness; nor when stricken did he utter a word, nor did he let out a cry or a sigh, or a sign signaling any kind of pain; instead he held still the head that he had bent toward the unsheathed swords. As his body — which had been mingled with blood and brain — laid on the ground as if in prayer, he placed his soul in Abraham’s bosom. Having risen above himself, without doubt, out of love for the Creator and wholly striving for celestial sweetness, he easily received whatever pain, whatever malice, the bloody murderer was able to inflict. And how intrepidly — how devotedly and courageously — he offered himself for the murder when it was made clear that for his salvation and faith this martyr should fight for the protection of others so that the affairs of the Church might be managed according to its paternal traditions and decrees. The famous medieval chronicler, Gervase of Canterbury, who knew Thomas Becket, is our eye-witness as to how Becket’s clothing revealed his penitential nature: His dead body was removed and placed in the shrine before the altar of Christ. On the morrow it was carried by the monks and deposited in a tomb of marble within the crypt. Now, to speak the truth — that which I saw with my eyes, and handled with my hands — he wore hair-cloth next his skin, then stamin, over that a black cowl, then the white cowl in which he was consecrated; he also wore his tunic and dalmatic, his chasuble, pall, and miter; Lower down, he had drawers of sack-cloth, and over these others of linen; his socks were of wool, and he had on sandals.

.

The Golden Legend, written in A.D. 1275 by Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa, relates the tale of how the Pope came to know of Thomas’s death:

.

The Pope would daily look upon the white chasuble that S. Thomas had said Mass in, and the same day that he was martyred he saw it turned into red, whereby he knew well that that same day he suffered martyrdom for the right of holy church, and commanded a Mass of requiem solemnly to be sung for his soul. And when the quire began to sing requiem, an angel on high above began the office of a martyr: Letabitur justus, and then all the quire followed singing forth the mass of the office of a martyr. And the Pope thanked God that it pleased him to show such miracles for his holy martyr, at whose tomb by the merits and prayers of this holy martyr our blessed Lord hath showed many miracles. The blind have recovered their sight, the dumb their speech, the deaf their hearing, the lame their limbs, and the dead their life.

.

The murder outraged all of Europe, and pilgrimages to the site began almost immediately, with miracles following in abundance. He was canonized in 1173. King Henry repented and made public penance at the tomb, allowing himself to be scourged there. Canterbury became the third greatest site of pilgrimage in all of Europe (Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” concerns pilgrimage to his shrine). His relics are said to have been destroyed in 1538 during the Protestant rebellions foreshadowed by King Henry’s attitudes, but some believe that a skeleton found in the crypt there in 1888 belongs to the martyr.