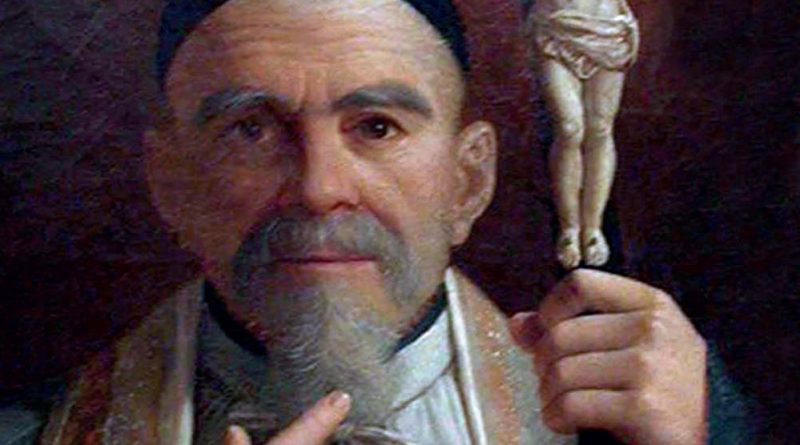

Saint Francis Regis Clet Lazarist Missionary and Martyr (1748-1820)

Born in 1748, Francis was the son of a merchant of Grenoble in France; he was the tenth of fifteen children. The family was deeply religious, and several of its members were already consecrated to God. Francis attended the Jesuit college at Grenoble, and in 1769 entered the novitiate of the Lazarists, a missionary Community founded by Saint Vincent de Paul. He was ordained a priest in 1773, then taught moral theology in a diocesan seminary. In 1789 he was named director of the Lazarist Seminary in Paris but was obliged by the fury of the revolution in that year, with the entire Congregation, to abandon the mother house.

.

Saint Francis exposed his desire to be a foreign missionary to his superior, and was sent by him to China in 1791; there he labored for 28 years, entirely alone for several years in a vast district. Death had deprived him of his two brother-priests. Persecutions in 1812 and 1818 destroyed his church and schoolhouse, and he himself escaped several times, as it were by miracle, from searching parties. But he was finally betrayed by a Chinese Christian for a large sum of money and seized in June of 1819.

.

For five weeks he endured cruel tortures in total silence, then was transferred to another prison, where he found a fellow Chinese Lazarist from whom he could receive the Sacraments. His death sentence was pronounced in January of 1820, and he died in February of that year, strangled while tied to a stake erected like a cross.

.

AN HEROIC SACRIFICE.

.

The truth is that it is very difficult for us to understand the greatness of the sacrifice, and how friendless, hopeless, and threatening was the prospect before him. The voyage from France to Macao, by the Cape, was some 18,000 or 20,000 miles. It took six months, and sometimes more. Ile missionary had first to face this tremendous voyage. He had to make it in a sailing ship, amid discomforts of every kind. The ship was small, the quarters narrow, the food dry and salt, the water bad and scanty ; they had to cross the line twice ; and had to encounter the stormy waters of the Cape. The disease was constant on board, and deaths were common. There are many tender and sensitive hearts 1.0 whom it is martyrdom already to bid adieu to friends, to leave their pleasant native land, to shut themselves up in the tossing prison, and to turn to the long, tedious, hopeless voyage that is to interpose between them and all that they have held dear—those thousands of leagues that they can never again hope to repass. How often in the long days, in the storm, in the sweltering calm, in sickness, in the star-lit nights of the Pacific the heart of the missionary must have lifted itself to God and realized the shadow of His hand. He had cut himself adrift from the country, from family, from religious brethren, from Christend0m-7 even, in a sense, from the Church herself. A renunciation like this tests the spirit of a man. He that can accept such a condition is the one who is fitted to preach Jesus Christ to the heathen. No man indeed can follow Christ at all unless he is prepared to give up—to renounce; and the nearer a man is to be to his Saviour the more complete must be his renunciation. We have no record of the aspirations of the heart of this holy missionary on that long and hard voyage, but he was already a man of interior life, spiritual, and experienced in the ways of the Holy Ghost. Remembering this, and knowing what be was to be in the future, and how he was to lay down his life for his Master, it is not mere fancy to suppose that those months of life on ship-board were months of retreat—such a retreat as he had never preached or practised before; that he learned ” in that day,” as the prophet spoke long ago, “to lean on the Lord his God in very truth” (Isaias X., 20) ; that he underwent one of those conversions which come, by God’s grace, even to those already given to God, and began to comprehend what Jeremiah meant when he exclaimed, “The Lord is my portion, said my soul” (Tbren. iii., 24); that his courage rose as the distance grew less between himself and his labour, and that before he landed he had accepted all that was to come—all that was repugnant to nature— had ceased to hesitate, ceased to fear, and was crying out with St. Francis Xavier, “Yet mine, 0 Lord, yet mine “

.

We are not able to follow Father Clet in his voyage to China. There is one letter extant, written at sea, and dated July 2, 1791. exactly three months after his embarkation. From it, we learn that the vessel was then becalmed off South Africa, and was awaiting a wind to double the Cape. Perhaps the letter was sent ashore at Cape Town, then a small settlement and port, in the possession of Holland. Nothing more is heard of him until we find him at Macao. Macao is a town on a very small island off the mouth of the Canton river, not far from Hong Kong. But there was no Hong Kong then, as we know it; there was no British settlement till fifty years later. Macao was, and is Portuguese territory; it was thence that the Portuguese prosecuted their trade with Canton. St. Francis Xavier, 250 years before, bad been in those very seas; not at Macao, for the island did not then belong to Portugal; but at Sancian, not many miles south. It was from these that the Apostle of the Indies tried to find the door of China, and it was there, having been permitted only to look towards the land he sighed to save, that he laid himself down under a rough shelter, and gave up his soul to God. Since then, through his intercession, Catholic missionaries had penetrated the country; and now, whilst Europe was in a tumult of confusion and of war, Father Clet and his two companions disembarked among a Catholic people, to prepare for the final stage of a journey that was to lead them into the heart of an empire where Christianity was as rare as the scattered islands in some vast Atlantic.

.

The three missionaries stayed some months rt Macao. Father Clet’s companions were here ordained to the priesthood. All three began to study Chinese. It was not till September 1792, that is, a year and a half after his departure from France, that we find him on the spot where he was to labour. We have a letter, dated October 15, 1792, in which he says to his sister: ” This scrap of a letter is merely to let you know that I have arrived at the place of my residence in good health. The journey took thirty days, and I was not recognized once.” For, although there was no actual persecution raging in China at that moment, no Christian, and especially no foreigner, was ever safe from the mandarins or the mob. He had, therefore, to travel in disguise.

.

Traveling thus alone, at the mercy of enemies and faithless friends, he passed through the wide country lying between Canton and his appointed sphere. We find then our blessed missionary, in the middle of October, 5792, arrived at last upon the field of his mission. He first settled in the province of Kiang-Si; but after a year in that province he went, at the request of his superiors, into what is now the Province of Hompeh—a name that will be recognized. The mission itself was in a mountainous and wild country—but it was within a short distance of the Yangtsze, the busiest and most fertile portion of the Empire, and of the great inland sea of Tung-Sing. It was in the neighbourhood of a large village called Koa.tching that Francis Clet lived for twenty-seven years. That name also will perhaps be recognized in this church, for it was there some fifty years later that the Blessed John Gabriel Perboyse laboured, and it was there that his martyrdom began. It might be enough, my brethren in Jesus Christ, to state in simple words that the Blessed Francis Clet laboured by himself in the heart of the Chinese Empire for twenty-seven years without once leaving the country and that he was _finally martyred where he had lived. There

.

are few of us with souls so dead as not to be able to feel what those words mean—the desolation, the silence, the fidelity, the perseverance. But it is a duty of devotion for you and for me to dwell a little on such details as we have, that so we may thank God the more fervently on this day for the blessed martyrs whom we celebrate. Let us contemplate him then living in the shadow of the hand of God.

.

THE VASTNESS OF THE FIELD.

.

First of all think of that French priest, dropped like a stone into the sea, into the midst of the vastness of China. Among a people numbering 400,000,000—a figure no imagination can grasp—there were a few hundreds—or let us say a thousand or two—of native Christians among the rocks and glens of the Yangtsze Htghlands. In a few other localities, widely distant from one another as London from Petersburgt, you found a similar colony. At Pekin there was more to stow; for there, around the Emperor’s palace’ the Jesuit Fathers had extorted a kind of recognition, and by their learning made themselves indispensable to the capital. But Pekin is a thousand miles from the Yangtsze Valley. The Chinese mission is poor enough and relatively small enough even in our own day; but there are at this moment five Vicars-Apostolic exercising jurisdiction over the district which was in the sole charge of the Blessed Francis Clet. Neither did he enter on a field where the harvest was promising, even if scanty as yet. There had never since the first beginnings been a moment when the fortunes of the Chinese mission field seemed at a lower ebb. The missions had virtually been altogether in the hands of the Society of Jesus, which, decade after decade, had poured men into the country. The Society had been suppressed in 1773, eighteen years before our missionary sailed from France. At once the source of supply was cut off. The Holy See, indeed, was alive to this disastrous result. But years passed by before the Pope and the King of France together could arrange for the Congregation of the Mission to take the place of the Fathers of the Society. The first Lazarists had entered the country only seven or eight years before Francis Clet himself. Meanwhile, the ex-Jesuit Fathers had been dying off, and the survivors growing old. The Christian congregations, being gradually deprived of their pastors, had in many places begun to lose their faith, to revert to heathen ways, to dwindle in numbers. There Lad been bitter and sudden persecutions such as are always happening in China. And altogether it seemed as if the name of Christ was about to be swept from the land. Francis Clet may have thought so. But for all that, like the soldier of a forlorn hope, he went to his work, under the shadow of the hand of the Lord.

.

Now let us see him in the heat and toil of his apostleship. I gather a few details from his own letters. Remember he was virtually alone. For twenty years and more, he had not the consolation of the company of a European brother priest. When he was not on his long rounds of visitation, he lived in a poor hut which he used to call his “mansion of straw.” His poverty was always extreme. No doubt, as a rule, the rice and oil and salt and other things which he absolutely required were supplied him by his flook. But they were all poor labourers, and few of them bad enough to live upon themselves. His bed and clothing were of the humblest kind. The winters were severe, and in the summer, for many weeks the heat was so excessive that be had to remain under cover. His journeys were made chiefly on foot. He had i.o be away for months at a time, traveling from one Christian settlement to another, to baptize, to hear confessions, and to instruct. When he was at his “home,” so to call it, he had many hundreds of children around him. The services of the church were fairly carried out, and we read, that on one Good Friday about 1,000 worshippers attended the solemn offices. The work of a missionary in China consists, in a great measure, in instruction. To know bow to instruct—to attempt neither too much nor too little—to get the children, the young people, and the parents to attend regularly, and to keep all this up successfully when there is only one priest for a whole province, requires skill in organization, daily hard work, and dogged perseverance. This laborious duty you must picture to yourselves the Blessed Francis Clet carrying on day by day in the bamboo shed which served him for church in the billdistricts of Central China. This work and that of the confessional, with the visitation of the sick and dying, he discharged with such conscientious exactitude that his health gradually broke down. He must have been a strong man when he left St. Lazne, for the sea voyage was .nothing to him, nor the yet more trying land journey, and he makes nothing of the new life and hardships that he first encounters. Neither does he ever seem to have actually ceased work except in one severe Illness. But he grew emaciated, his feet and legs gave way, and long before he was seventy he was in habitual suffering and an old man.

.

“My MINISTRY IS NOT BLESSED.”

.

My own view, formed from an attentive study of all that has come down to us of the missionary career of Blessed Franc’s Clet, is that during the whole of those twenty years he was struggling against discouragement. He thought he was a failure. There is no heavier cross than this. Yet there is nothing that is more blessed by God when it is lovingly accepted. St. Vincent de Paul has this truly spiritual saying: “One of the most certain maiks that God has great designs upon a person is when he sends desolation on desolation, suffering on suffering.” The Chinese Christians, of whom our holy missionary had the care, had been without a priest for four or five years. They had been terrified and demoralized by persecution. Their faith was slipping away, and their Catholic practice dying out. It would, indeed, have been miraculous, in a country like China, where religion is inextricably mixed up with nationalism, with loyalty, and with social fellowship, to fied Christians keeping their Christianity without the constant and strenuous help of a pastor. Francis Clet not only made few converts but bad to mourn the loss of many already baptized. He knew—and said—that he could do little to make a Chinese a self-suffering Christian. They were all children; leave them to themselves even for an instant and they might be expected to fall back into carelessness, superstition, or downright heathenism. Again and again, in his letters, there is a note of anguish—a cry that he was a useless servant. We must remember that no missionary in China could preach or minister openly. It was treason. The governors and magistrates might be forbearing and indulgent, and in remote places, with a considerable resident Christian population, the priest might venture outside in his priestly

.

dress. But at any moment general or local persecution might spring up, and the priests come to be bunted like wild animals from hole to hole in the rocky mountainsides. This life of toil—this life of physical hardship, unrequited labour, of apprehension, and of danger—was the life of Francis Clet for twenty-seven years. Towards the middle of it. he said: “My ministry is of the most ordinary kind, for my piety is very ordinary;” and again, “As I am not a man of prayer, my ministry is not blessed.” This is what he thought and felt.

.

One very touching circumstance, to which he alludes several times, is his inability to acquire Chinese. “I came out too late,” he said, “to be able to learn it even passably” (p. 530. “All I know of it is barely enough for the common intercourse of life, to hear confessions and to say a word or two to our people; still, ignorant as I am, it is better for them to have me than to have no one” (p. 135). “Considering my difficulty with the language,” he writes later, ” I am inclined to think I should have done better bad I stayed in Europe. But I have one spiritual advantage in being in China—that, whereas in my own country I might have thought myself good for something, here in China there is the clearest evidence that I am good for nothing” (p. 136). No one else thought so. It is only the humility of the saint. But words like these show what kind of a cross he had to carry. Let me mention one other element of his discouragement. He had the greatest dislike to the ministry of the Confessional. In 18o9, he wrote these words to a confr4re: “For eight or ten years I have longed to be relieved of the weight of the mission, in order to devote myself to the formation of church students, because the ministry of the Confessional has always been for me an overwhelming burden. . . . The Confessional is my cross; perhaps God wills that I should bear it to the end; may His holy will be done” (p. 289).

.

There, my brethren in Jesus Christ, you have a glimpse of the inmost soul of Francis Clet. There is n a time now to enlarge upon his natural character, such as we find it indicated in the few letters of his that have come down to us. He was a strong, solid, loyal sou of Eastern France; a man of calm reflection and prudence; unemotional, yet not without a certain dry and quiet humor; a priest through and through, with all a priest’s training and feeling; without brilliant talents, but eminently capable in matters spiritual and temporal; extremely sensitive of con

.

science. and absolutely true and straightforward. I do not know whether it will disappoint you if I say that the visible results of his twenty-seven years’ apostleship seem to have been only ordinary, and by no means marvelous. Do not misunderstand. He entirely changed the face of his home mission; he kept thousands of converts up to their religion; he organized effective mission work over an immense district, and be left behind him memory and a name, which, long before any proceedings began for his beatification, lived in the veneration and the affection of Catholics and pagans. But, for all that, I venture to say of this hero of the cross, that his success in life was not more than ordinary; and I believe that his beatification is a wonderful, inspiring and consoling lesson to the great army of missionaries; a revelation of the way in which God works; an illumination, vouchsafed to these latter ages, to guide and lift up the hearts of those who are called by God to “plant the heavens and to found the earth.”

.

WHAT IS FAILURE?

.

There is only one Francis Xavier in a century, or in a round of centuries. There are wonder-workers in the mission field only once or twice in a hundred years. There are wholesale conversions and stupendous successes only rarely in history. But the heroes of the

.

mission are at work all the world over, in every season, day after day, till they drop. No one knows about them, no one talks about them; a letter or two comes to Europe, a name here and there becomes known, and, at times, we hear of persecution’ devastation, and violent death. But all the time, on every pestilential coast, in the heart of barbarian continents, among the foremost of the pioneers of civilisation, and amid the immemorial monuments of the obscure and changeless East, the Catholic missionaries are quietly labouring, instructing, imparting the sacraments, lifting up the sacrifice. Not one in a thousand of them will have his history written. Yet there is a story for every man—of zeal and suffering, of converts made and souls saved. They are heroes, they are saints, they are martyrs. They are known to God.

.

But today, as it seems to me, the great Master of all missionaries has singled one out in order to let us all understand what is the glory and the crown of every true missionary that carries his name to the heathen. Francis Clet, as we know, was a martyr; his virtues were heroic, and miracles have been wrought by his prayers. A man, therefore, maybe all this without the success or the wonder-working of a Francis Xavier. This beatification seems to light up the lives and deaths of all that great company who serve the missions of the Catholic Church. This solemn Beatification should, therefore, reach the heart of every missionary now at work throughout the world, and should sound like the note of a trumpet in the ears of every fervent seminarist and novice who is preparing to go to the front, where Christ’s battle never knows a truce. To be a real missionary is lobe a true Saint. Whether you succeed or whether you fail the obedience, the zeal, the hardship, the perse-verance—the very life itself, will stamp heroic sanctity upon your soul. Whether you work miracles or not your crown is that of the confessor. Whether you testily before kings or die with your confrire’s blessing amid your children’s tears, you merit the aureola of the martyrs.

.

But there is another lesson in this holy man’s life for every missionary and every Christian who prays for and helps the missions. How do we know that his mission, after all, has been a failure, even in the modified sense in which we spoke just now ? What do we mean by success ? I look upon the three years’ ministry of Jesus Christ, and I ask myself in what lay the triumph of His word, of His Cross ? To answer that question one must climb high and look out afar over the centuries, and the generations, over the countries of the earth and the races of men. One must enumerate all the victories of the Gospel from the day of Pentecost to the world’s passing away. One must sum up all history, and analyze all the movements of mind and will in the story of the world’s vicissitudes. For it is the lowliness, the toll, the patience, and suffering of Christ that have brought about the triumph of His Smoothie Kingdom.

.

The lesson is plain. A Christian’s success is his likeness to Christ: a missionary’s success is his spirituality, his hidden life, his desolation, his share of the Cross. It is nothing that, during the brief space of his earthly struggle, few souls inclined to him, and God’s interests do not grow. The triumph is certain to come. The harvest is to ripen in another generation and under different skies. The missionary may water with his blood and his sweat the soil of Central China, and the grace of God may be given to a people in the valleys of far-off African rivers, or in remote islands of the Indian Ocean, or in the lauds where Mahomet holds men in thrall. He may offer to his Heavenly Father a decade or two of the years of the nineteenth century, making his sacrifice acceptable with his prayer and his tears; and behold ! when a new century has half run its course, and God sees that the hoar has come, there is a success, there is victory; the Kingdom of Christ gains ground, and the saints rejoice—and the price of it all was paid in those obscure years so long before. For ” the oblation of the just is an odour of sweetness in the sight of the Most High . . . and the Lori will not forget” (Ecclus. xxxv., 8, 9). Not a sparrow falls but the Lord knows it—not a hair of the bead shall utterly perish. Not a step of those painful journeys, not a word of those devoted instructions, not an hour of all that crucified life will He ever forget. They are all laid up in the treasury of the King—precious, efficacious, carrying with them the promise, the power, the fruit. And the more that missionary life has been conformed to Bethlehem, to Nazareth, to Calvary—the deeper has been the obscurity, the more complete the humility of obedience, the more bitter the chalice of interior and exterior suffering, the more glorious will be the harvest. For the shadow of the Almighty Hand that was over His servant even from the beginning is not as a fleeting cloud which lasts the day and is dissipated with the set of the sun, but it watches on, swaying the seasons and scattering even for the sake of that servant who is gone.

.

THE LAST TESTIMONY.

.

The martyrdom of the Blessed Francis Clet was like the rest of his life—obscure, painful, perfect, and complete. Being seized, he was -dragged from prison to prison, interrogated, beaten, and, to some extent, tortured. Yet it is curious to note—and it is of a piece with the rest of his honest, loyal, straight life—that he finds, according to his own letters, many friends in his imprisonment, both Christians and heathens, both fellow-prisoners and magistrates and gaolers, and that he wrote, in the very last months of his life, and while in prison, a memoir which he wished to be published anonymously in France, comparing the prisons of China with those of his own native Christian land, very much to the disadvantage of the latter. At last, the edict came from Pekin; his companions were released, but he was to die. One morning very early—it was February 18, 1820—a day of snow and damp and cold—the satellites came to his cell and bade him follow them. “Am I leaving for good ?” said the martyr. They hesitated. “Tell me the truth,” be insisted. Then they admitted that he was to return no more. Thereupon the face of the holy missionary lighted up with joy. He begged for one instant’s delay and turned to a fellow priest for a last absolution. The soldiers tried to make him put on better clothing than the old and ragged garments he was wearing. But he said he would like to die, not as a martyr, but as a penitent. Then he said a word to the Christians who had come round him and were weeping bitterly. He told them they should rejoice that he was to have the happiness of dying for Jesus Christ. “Serve God fervently,” he said, “and never give up your holy faith.” He was to die by strangulation. They took him outside the town, to the commonplace of execution. There a gallows was erected in the form of a cross, like that on which Blessed John Gabriel Petboyre suffered. They let him pray for a few moments; then he offered his hands to be bound, and he was tied up on the cross. Strangulation ought to be a short and easy death, but the Chinese executioner knew how to make it painful, and there is reason to believe that Francis Clet underwent a long and cruel agony, and after death, his body seems to have been trampled on by the executioner. But like the rest of his life, this last scene was shrouded from sight, in the half-light of a winter’s morning, the few spectators being kept at a distance by the snow and the mud. But God saw it all. And so his soul passed to God, and his worn-out body fell on the soil of China, to be the seed of the harvests of heaven.

.

In 1869, his precious remains were brought to France, in spite of the efforts of the native Christians to keep them; they now repose near those of Blessed John Gabriel Perboyre, in the mother-house of the Vincentian Fathers in Paris.

.

Prayer to Venerate Any Saint

.

Saint Francis Regis Clet: Feast Day February 17

Rev. 8:3-4 [3] And another angel came, and stood before the altar, having a golden censer; and there was given to him much incense, that he should offer of the prayers of all saints upon the golden altar, which is before the throne of God. [4] And the smoke of the incense of the prayers of the saints ascended up before God from the hand of the angel.

ETERNAL Father, I wish to honor St. (Name), and I give You thanks for all the graces You have bestowed upon him (her). I ask You to please increase grace in my soul through the merits of this saint, and I commit the end of my life to him (her) by this special prayer, so that by virtue of Your goodness and promise, St. (Name) might be my advocate and provide whatever is needed at that hour. Amen.

PROMISE: “When you wish to honor any particular saint and give Me thanks for all the graces I have bestowed on that saint, I increase grace in your soul through the merits of that saint. When you commit the end of your life to any of the saints by special prayers, I appoint those saints to be your advocates and to provide whatever you need at that hour.”-Our Lord to St. Gertrude

Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich revealed in her Visions that saints are particularly powerful on their feast days and should be invoked then.